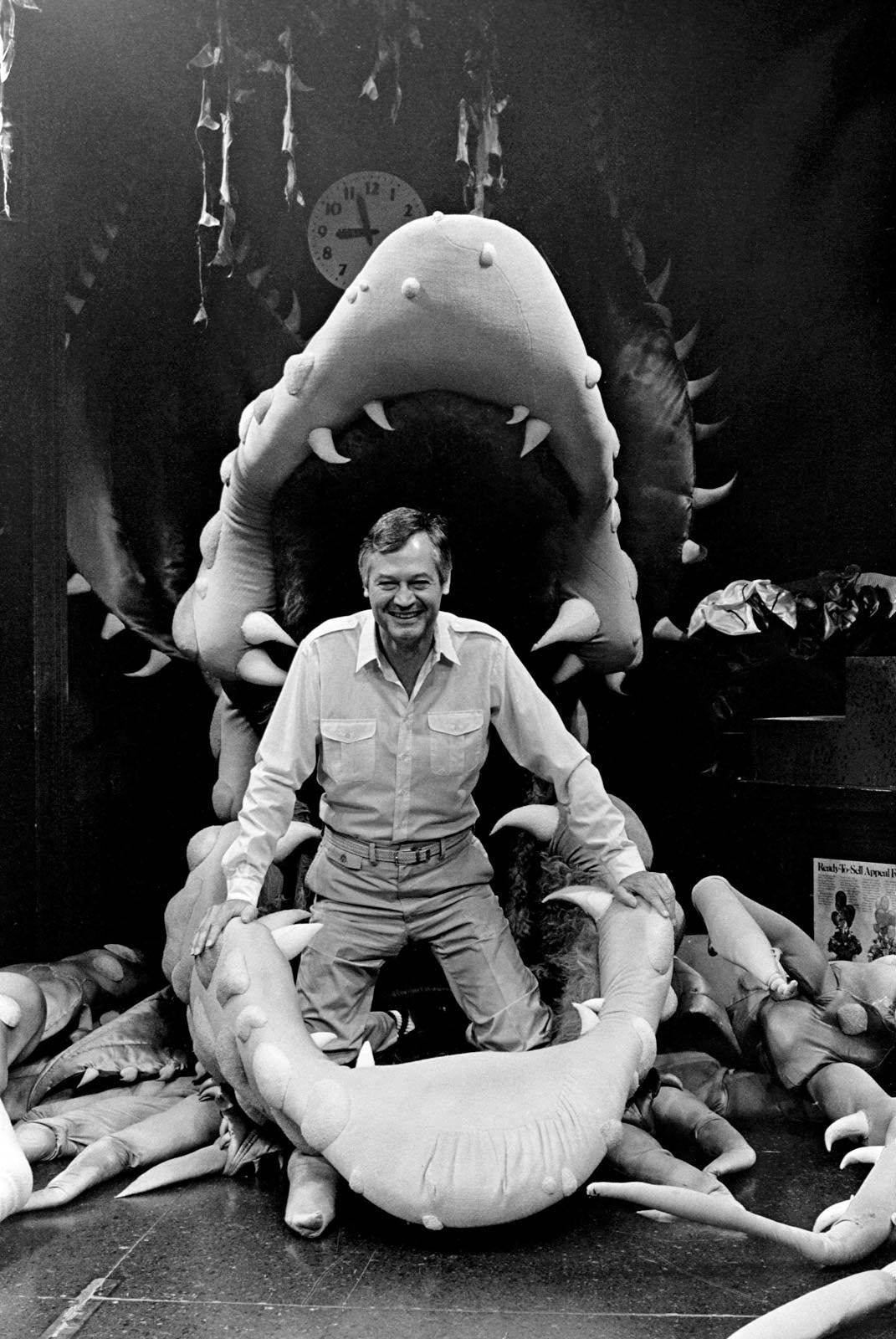

Roger Corman (1926-2024)

"If you do this picture correctly, you'll never have to work for me again."

Roger Corman, who died last Thursday at the grand old age of ninety-eight, was the kind of filmmaker whose contribution to cinema always feels like it needs a series of explanatory footnotes, caveats, and apologia. His profligacy as a director and producer tends to bamboozle auteur-centric critics in need of the “quintessential Corman” picture, usually resulting in a reluctant shrug of acknowledgement rather than a considered retrospective.

Yes, they say, he was influential, but was he good? Had Corman not been restricted to low budgets, exploitative storytelling, and short shoots would he have been one of the greats? Fundamentally, how can we possibly praise the man behind Attack of the Crab Monsters (1957) and She Gods of Shark Reef (1958)? Wasn’t it all bad rubber monsters and scantily-clad scream queens?

Sure, there were wobbly creatures and wobblier performances. Later, there would be dodgy CGI, portmanteau monstrosities like Dinosharks, Pteracudas, Whalewolves, Supergators and Piranhacondas, and more Death Races than you could feasibly shake a stick at. But those were Corman’s bread and butter movies, an easy churn of cheap franchise films to keep the fires stoked. And some of them - I’m looking at you, Death Race 2050 - are a lot of fun, which is in arguably short supply these days.

Even if we restrict Corman’s contribution to his directorial credits, we still have the wonderful Poe Cycle, a series of films that not only reinvented the brooding Gothic horror for the ‘60s (in America, at least1), but also (re)introduced the likes of Vincent Price, Boris Karloff and Peter Lorre to a generation of budding cinephiles. Then there’s his ahead-of-its-time white supremacist thriller (and notorious flop) The Intruder (1962), obvious precursors to Easy Rider in The Wild Angels (1966) and The Trip (1967), and a couple of genuine camp classics in A Bucket of Blood (1959) and The Little Shop of Horrors (1960). I also have a peculiar soft spot for Frankenstein Unbound (1990), a strange little sci-fi horror based on a Brian Aldiss novel that happens to have a great cast (Michael Hutchence as Shelley!) and a delightfully offbeat sensibility.2

What comes across in all these films is Corman’s love of filmmaking. He was, more than anything else, a cineaste with an unerring eye for talent. The list of graduates from The Roger Corman Film School is a Who’s Who of ‘70s and ‘80s Hollywood, and while it’s arguable that the likes of Coppola, Scorsese, and Bogdanovich would have made it anyway, they certainly wouldn’t have had the level of on-set experience without Dementia 13 (1963), Boxcar Bertha (1972) and Targets (1968). John Sayles managed to finance Return of the Secaucus 7 (1980) thanks to his screenwriting jobs on Piranha (1978) and Alligator (1980). Piranha also marked the first sole directorial credit of Joe Dante, without whom a generation of kids would have remained unscarred and less interesting. Robert Towne - the New Hollywood screenwriter - made his bones on Corman’s The Last Woman on Earth (1960) and his work on A Time for Killing (1967) brought him to the attention of Warren Beatty. And who else but Corman would take a chance on a biker Rashomon script by a twentysomething Jonathan Demme or an adaptation of Charles Willeford’s Cockfighter?

This doesn’t even begin to scratch the surface of influence Corman had on 1970s cinema, not just the directors, producers, and writers, but also the actors. The stars of the ‘70s usually had some connection with Corman, whether it be the obvious examples of Jack Nicholson, Peter Fonda, and Bruce Dern, or lesser known actors like Diane Ladd, Talia Shire, and a persistent little fella by the name of Sylvester Stallone. There’s a reason why Corman found himself referenced3 or asked to perform cameos4 in his protégés films: he was the reason many of them had careers. And that pay-it-forward ethos continued: Monte Hellman’s guiding hand on Tarantino’s Reservoir Dogs (1992) or Jonathan Demme’s overwhelming influence on Paul Thomas Anderson spring to mind.

It wasn’t just American filmmaking that owed him a debt: without Roger Corman’s distribution deals and marketing savvy, many filmgoers wouldn’t have encountered the likes of Bergman’s Cries and Whispers (1972), Fellini’s Amarcord (1974) and Kurosawa’s Dersu Uzala (1975)5. For all his exploitation movie career, Corman was a dedicated cinephile and - with a little more support - might have managed to strike that balance between high and low culture. Indeed, some of his mooted projects during his short Columbia tenure included adaptations of Joyce and Kafka, and a script about Iwo Yima by the legendary Richard Yates.6

So it’s unfortunate that Corman’s legacy still has that whiff of exploitation about it. While it’s true that without Corman, we wouldn’t have similar self-styled impresarios like Lloyd Kaufman and Charles Band, neither of those (fine, upstanding) gentlemen have crawled out of the genre gutter long enough to have lasting impact.7 Not even Corman could boast a lot of new talent in his later movies (with some obvious exceptions like Timur Bekmambetov), but this is likely down to a lack of further opportunities within a dwindling studio system.

He may have wanted to be remembered as “a filmmaker, just that”, but Roger Corman was much more - a studio head with actual filmmaking experience, a talented marketer, an incredibly savvy businessman, and a guiding light for new talent. For all intents and purposes, Roger Corman helped create one of the most fertile decades in American cinema, launched the careers of some of the all-time greats, and managed to build a pretty impressive filmography of his own. He’s also one of the few people with a seven-decade career who felt like he had more to do - an oddly optimistic part of me hoped that he would revolutionise low-budget cinema once again. For now, the Roger Corman Film School has shut its doors; we can only hope that someone else takes up the mantle, because the film world is a worse place for his absence.

Where to begin: you can’t go wrong with the Poe movies, particularly The Masque of the Red Death (1964) (ideally with the director’s commentary), or you could revisit The Wild Angels (1966). For an overview of Corman’s career, you’re duty bound to watch Corman’s World (2011), not least for the heartfelt tribute from the otherwise ice-cool Jack Nicholson.

Let us not forget the impact of Hammer and Bava in the late ‘50s and early ‘60s.

Per Aldiss: “John Hurt and I did rather a lot of drinking off set. On one occasion I became convinced I was Frankenstein’s monster. Grappa plays such tricks. I admired Roger’s patience when filming. How calm he was. And a good tennis player.”

Tomb of Ligeia turns up in Mean Streets …

… and Corman played a senator in The Godfather: Part II, as well as turning up in many of Dante and Demme’s movies.

Or, if you’re feeling spicy, the Emmanuelle sequels.

By far one of my favourite writers, so I’m biased here. But for someone with an ostensibly trashy reputation, Corman did attract some top-tier writers including the likes of Richard Matheson, Charles Beaumont, and the aforementioned Brian Aldiss.

You could argue that Kaufman was instrumental in giving the world James Gunn. Whether that is a good thing or not, I leave to you to decide. I am ambivalent.

As a fan of Corman's films, I appreciated this!

Really enjoyed reading this! What an interesting career Mr Corman had. I recently wrote something about him too: https://timedgeworth.substack.com/p/the-astonishing-world-of-roger-corman?r=44736